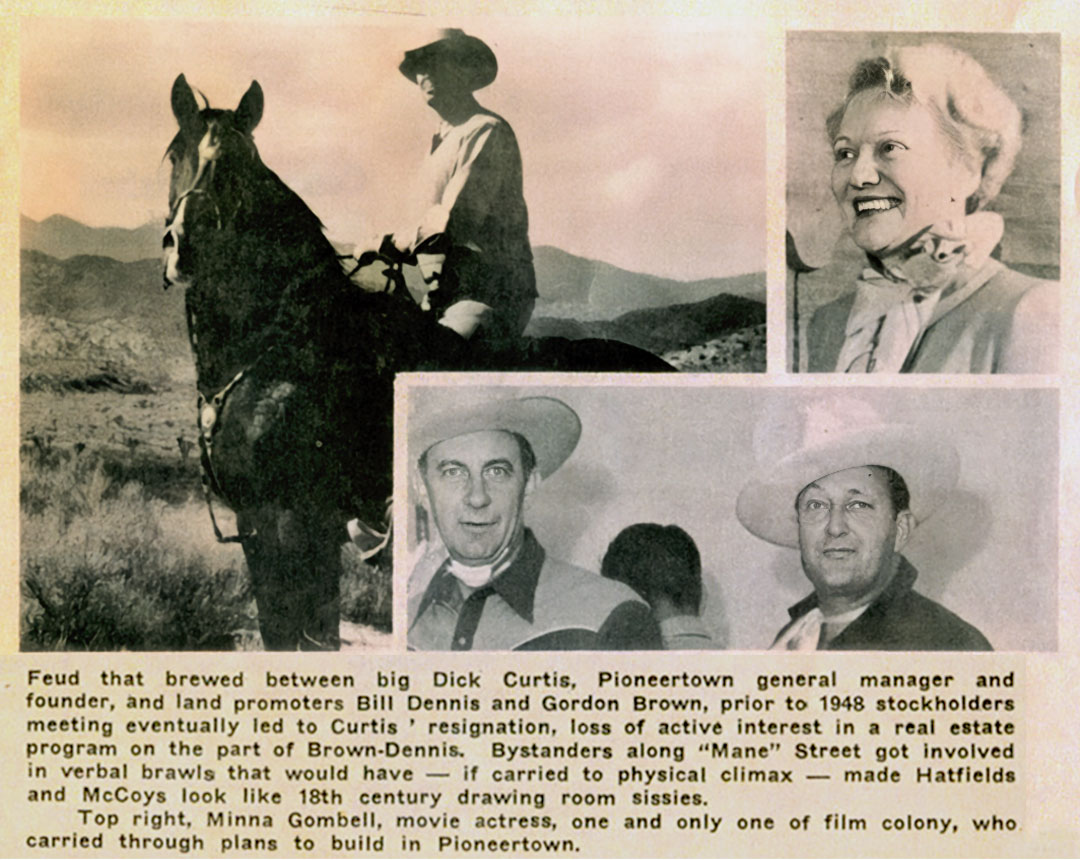

In the dry, wind-swept valley where the Mojave Desert brushes against the San Bernardino Mountains, a dream was forged out of sunburned skin, saddle leather, and old Hollywood grit. It was the dream of Dick Curtis — a tall, broad-shouldered Western movie villain with a devilish grin and eyes that carried the glint of a hundred barroom brawls. He’d been in nearly a hundred B-westerns, always the outlaw, always the man gunned down by the hero. But off-screen, Curtis yearned to be something more than a footnote in someone else’s script.

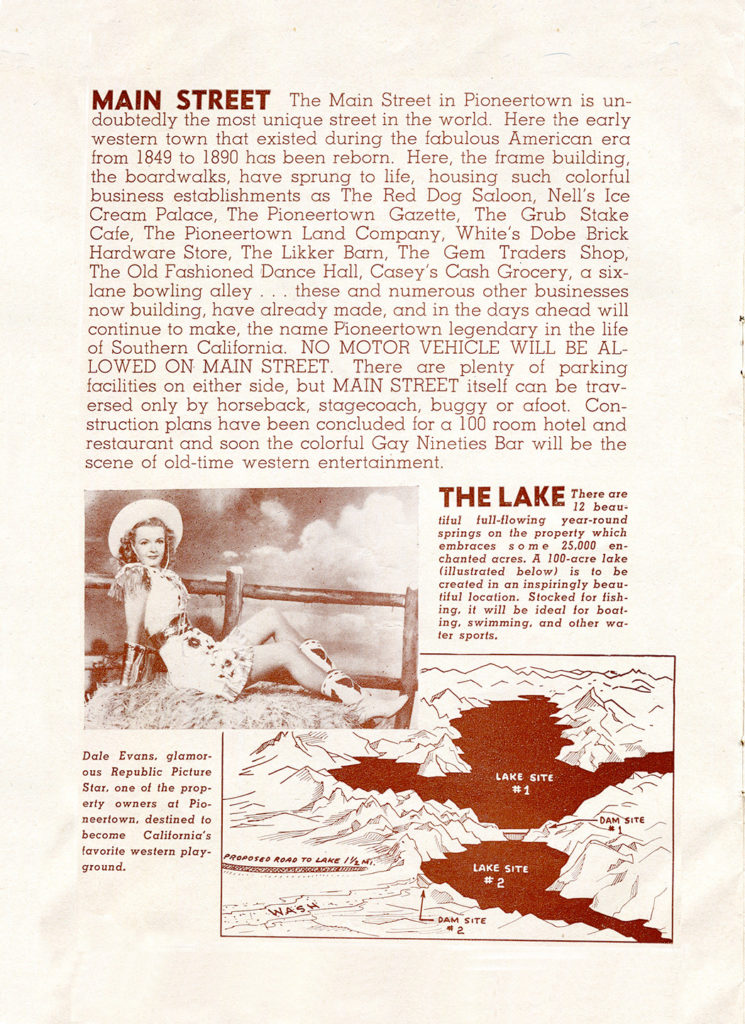

In 1946, with a sharp vision and the charisma to match it, Curtis convinced his movie-making friends — Roy Rogers, Russell Hayden, and others — to invest in a dream. An authentic Western town. Not just a film set with façades, but a living, breathing frontier settlement. Pioneertown. A place where actors could work, live, and ride out into the high desert sunset for real. Where fantasy bled into reality and back again.

Curtis saw saloons with real drinks, trading posts with real wares, and dusty streets where kids could grow up under the same wide-open skies that once echoed with cowboy yells and six-shooter fire. And for a short, blazing moment, it was his.

But dreams, like outlaws, draw the attention of the greedy.

By 1948, just two years after the town’s founding, Curtis was pushed out by developers he had once trusted. They wanted to commercialize Pioneertown, wringing profit from its charm. The partnership soured quickly and loudly — with eyewitnesses reporting screaming matches on Mane Street, Curtis red-faced, fist clenched, warning, “This town ain’t meant to be paved and poisoned!”

They took everything: his name, his control, his future. Broken and betrayed, Curtis faded from the project — a living ghost haunting a dream he’d built with his bare hands.

Curtis never recovered. He remained in the shadows of the town he built — his name slowly erased from deeds and brochures. In 1952, when the cancer finally took him, some swore it wasn’t the disease that killed him. It was the heartbreak. The soul-deep kind. The kind that doesn’t show up on X-rays but hollows a man out from the inside.

And that’s when the stories began.

The Curse Takes Root

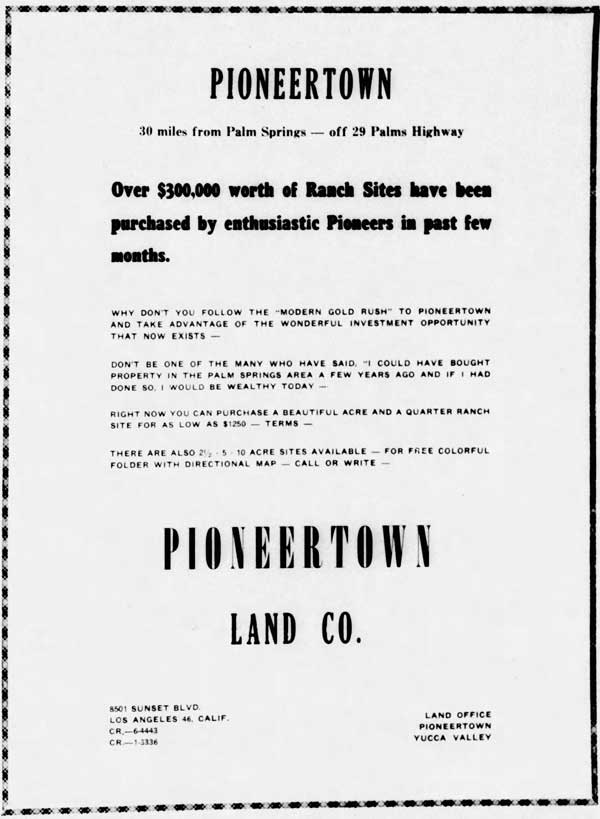

Within a year of Curtis’ death, the Pioneertown Land Company went bankrupt. The developers who muscled Curtis out fell to ruin. And from then on, Pioneertown became a place that chose its own, a place that rejected the greedy and sheltered the true.

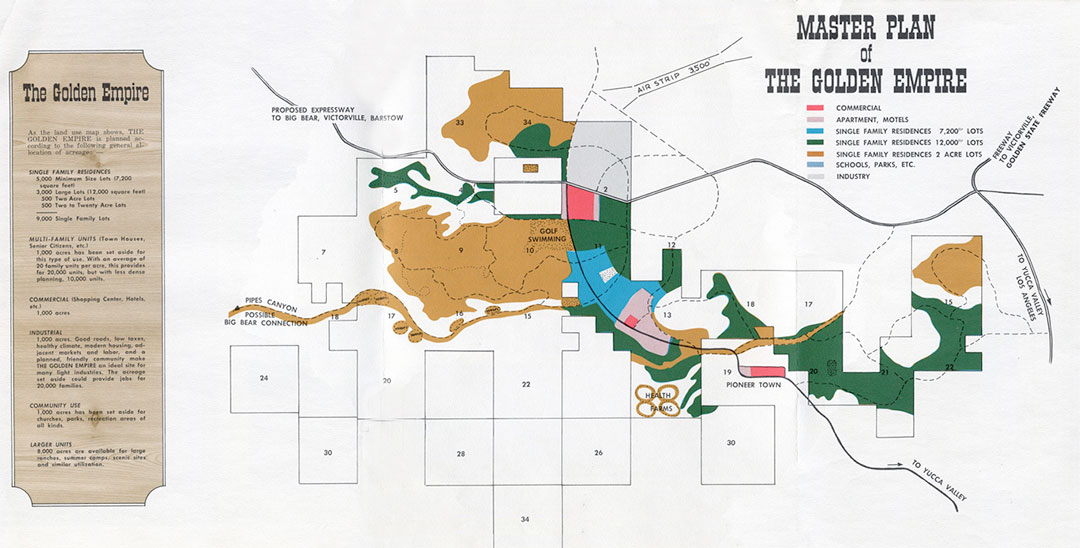

Then came the California Golden Empire project. A grand, glitzy development meant to transform Pioneertown into a glamorous desert destination: hotels, promenades, even talk of casinos. Investors were dazzled. Brochures printed. A health guru was convinced to promote the healthy air, soil, and water in Pioneertown.

Only one problem: a significant lack of water. When water was found, it showed high levels of arsenic and uranium. The project collapsed in disgrace, a would-be empire plans turned to dust, its backers fleeing with sunburns and lawsuits. The project was abandoned, just like Curtis’s dream.

People began to whisper that it wasn’t just bad luck. The desert — or something in it — was fighting back.

The 1966 Easter Week Fires

During Easter week in 1966, Pioneertown experienced three separate building fires that inflicted significant damage. Actor Jack Bailey had recently acquired the Golden Stallion Restaurant and the Pioneertown Motel with plans to expand and develop a resort. While battling the flames, firefighters from Yucca Valley witnessed something unusual. One firefighter recalled, “We were off to the side of the building, spraying water on the fire when the stallion turned and looked at us. Then it jumped into the flames.” Fire Chief Harry S. Brissenden commented, “Despite the intense heat from the fire, it gave us goosebumps.” The firefighters who fought the blaze at the Golden Stallion that Easter morning remained convinced that the life-size plastic stallion had come to life and leaped into the flames, marking the end of both the restaurant and the resort plans.

The original Red Dog Saloon/Cafe burned to the ground as well, The Red Barn, also known as the Likker Barn or Golden Spoon Cafe received significant damage. These fires removed the last of the businesses that brought people to Pioneertown. Only the Pioneer Bowl remained.

The Wild Years: Bikers, Burritos & Dust

In the 1970s, the town shifted again. A different kind of dreamer arrived — one with grit, humor, and a love for the land. She didn’t come with investors or architects. She came with faith in people and a respect for the place. Francis Aleba, with her husband John, converted a derelict old gas station into a rough-and-ready burrito bar, and Pioneertown became a magnet for outlaw bikers, exiles, and high-desert misfits. Mane Street echoed with the rumble of choppers and wild laughter. Bar fights became a local tradition. Tattoos replaced ten-gallon hats.

Yet even through the madness, the bones of Curtis’s dream endured. And so, the Curtis Curse slept — content, perhaps, that someone was finally honoring the spirit of the place.

The Music Returns: Pioneertown Palace

When the time came for a change, Francis handed the keys to the old cantina to her daughter and son-in-law.

In 1982, Francis’s daughter Harriet and her husband, Claude “Pappy” Allen, renamed the building Pappy + Harriet’s Pioneertown Palace.

The bikers didn’t vanish — but something shifted. Pappy brought his guitar. Harriet brought her heart. They served family-style Tex-Mex, cold drinks, and live music under desert skies. Their children often joined them on stage, creating a space where bikers, artists, families, and locals all shared the same tables.

Pappy + Harriet’s was rowdy, but it was real — and it thrived.

This wasn’t a business scheme. It was a family, with roots in the sand and music in their bones.

The curse didn’t touch them either. Because they never tried to take from the town, They gave to it. This family didn’t come for conquest. They came for peace. And so, the town embraced them. Curtis, it seemed, approved.

The Curse Lives On: AWE Ranch & the Developers’ Fall

But greed dies hard.

In the 2020s, the AWE Ranch project emerged — a massive proposal to build a 3,000-seat amphitheater, resort hotel, and luxury condos on the outskirts of Pioneertown. Investors promised culture, music, and luxury.

They were met with local opposition. This endeavor would threaten the fragile desert ecosystems, water tables, and the dark sky that made the town so sacred. And Curtis’s curse reared again.

A Town That Chooses Its Own

Pioneertown remains. Dusty, imperfect, beloved.

They began calling it The Dick Curtis Curse, not out of malice — but out of reverence. It wasn’t a curse of vengeance, but protection—a spiritual defense.

Locals whispered that Curtis’s spirit remained, walking the street he once fought to preserve. That those who came seeking fast fortune, who viewed the land as nothing more than acreage and opportunity, would find only failure. But those who came with respect, who wanted to live with the town instead of on top of it — they thrived.

Musicians found inspiration in the silence. Craftspeople built homes with their own hands. Small businesses flourished quietly.

Pioneertown welcomed them — like Curtis himself tipping his hat at the gate. Dick Curtis is still here. Watching. Protecting. Cursing where he must.

And blessing where he chooses.

Legacy Written in Dust and Smoke

Today, Pioneertown still stands — rough-edged, unpolished, and proud. The desert winds haven’t eroded the dream. They’ve only sharpened its edges. Mane Street is still there, flanked by false fronts and real stories. And when the wind is right, you might hear the clink of spurs on dry wood… and a low voice muttering about the price of dreams.

Dick Curtis may have died in 1952. But his town… and his curse… are very much alive.

And to any new developer with glossy renderings and sharp suits who asks, “Why doesn’t this place grow?” — the locals just smile.

“It grows,” they say. “But only for the right kind of people.” Those who arrived with respect — artists, musicians, craftspeople, and nature-lovers — thrive. They speak softly of the town’s history. They honored the spirit of what Pioneertown was built to be. And the town rewarded them. Businesses flourished. Communities grew. There is peace in the wind.

One long-time resident put it best:

“Dick ain’t gone. Not really. He’s just watchin’. And if you come here to build somethin’ good, somethin’ real, he’ll tip his hat to you. But if you come here to steal? You’ll hear his boots on Mane Street at midnight. And you’ll leave the way he did — with nothin’ but regret.”

“Respect the town, or ride on.”

That’s not a warning. It’s a promise.

And Dick Curtis keeps his promises.